Cephalium

This structure is the characteristic sign of the whole genus. Morphologically, it is similar to the Discocactus genus that also has a decorative central cephalium. Other thermophilic genera are adorned by a pseudocephalium, such as Buiningia, Coleocephalocereus, Austrocephalocereus, Micranthocereus and so on. Lateral cephalium is formed if the plant produces a mass of wool and bristles that are outgrown at the start of a new season, so the plant continues to grow with a new offset. A typical example is the Brazilian genus of Arrojadoa.

The forming of cephalium means the plant has matured. The body is fully grown and during the next stage of its adult life, the plant focuses on the growth of cephalium as well as blooming and fruit production. The cephalium protects flowers and fruits from premature picking by birds and other animals.

The blossoms are quite small and their colour only reaches the near red spectrum. The largest blossom is produced by the Cuban M. evae (3-centimeter wide). The club shaped fruit is either white, light pink, pink, red or purple.

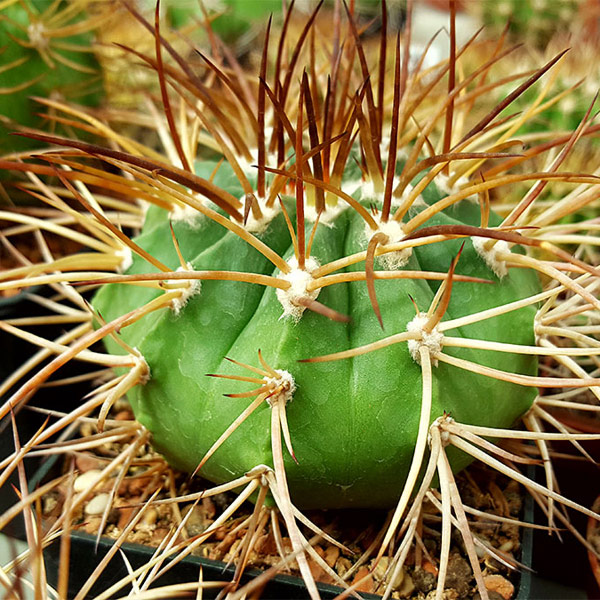

Melocactus caroli-linnaei

Melocactus caroli-linnaei

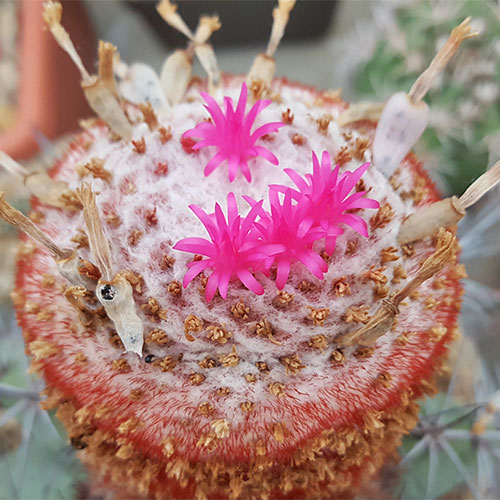

Melocactus matanzanus

Melocactus matanzanus

Melocactus azureus

Melocactus azureus

Genus Arrojadoa

Genus Arrojadoa

Melocactus evae

Melocactus evae